I should note before we get going that Disney+, the streaming service on which Andor is available, is currently on the BDS movement’s priority list of targets for boycott. I encourage you to investigate the BDS movement’s website and to consider cancelling any Disney+ subscriptions you may have.

After Disney’s brutal dismembering of The Acolyte, the only other Star War in recent memory to do anything interesting, my desire to write about Star Wars kinda fizzled. I watched a bit of Skeleton Crew, which seemed charming but minor, and I found that for the first time I didn’t really have anything to say about it. The triumphal return of Andor is about the only thing that could drag me back though admittedly it was touch and go – not till the 9th episode was I sure I’d have a go. With only the horrible Mandalorian and Baby Yogu on the horizon and the promise of a second miserable season of Ahsoka yet to come, Star Wars is on seriously thin ice. In my brain, at least.

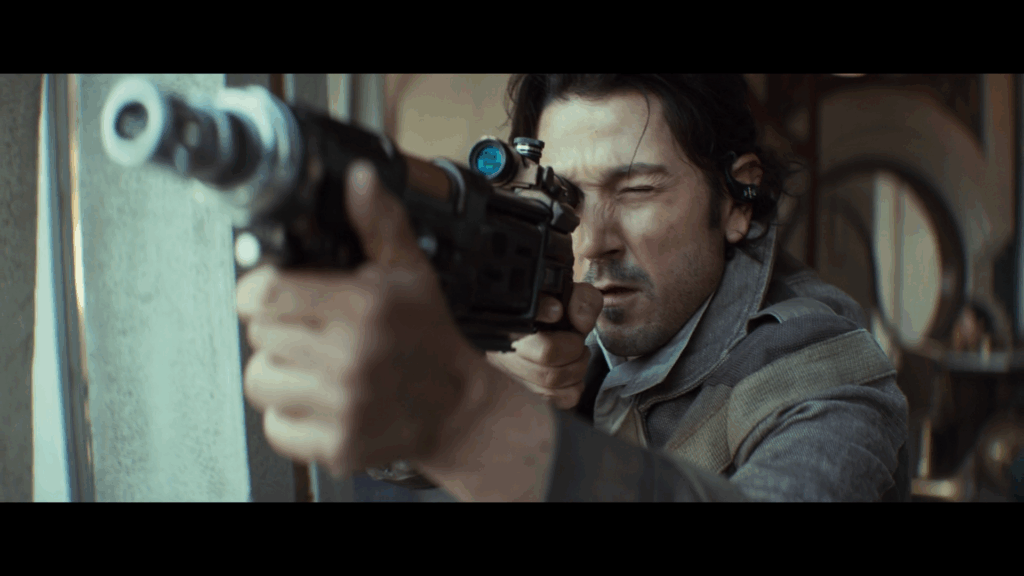

We left off at the end of Andor‘s first season reflecting on how neat a bow that run of episodes had tied; a continuation was by no means assured and so the major jigsaw pieces of how Diego Luna’s cold-blooded rebel hero would end up as the pseudo-protagonist of Rogue One were already in place. Incipient acts of rebellion; coordination of multiple autonomous groups; support from those in the existing structures of power. A second go round, then, would be sufficient if it merely filled in the gaps. And the structure of this project matches this ambition – four feature-length runs of three episodes each skipping a year, which like the first season vary in affect between “this is just a movie” and “this is a tight 50 minute showcase” – episodes 8 and 10 being particular self-contained standouts.

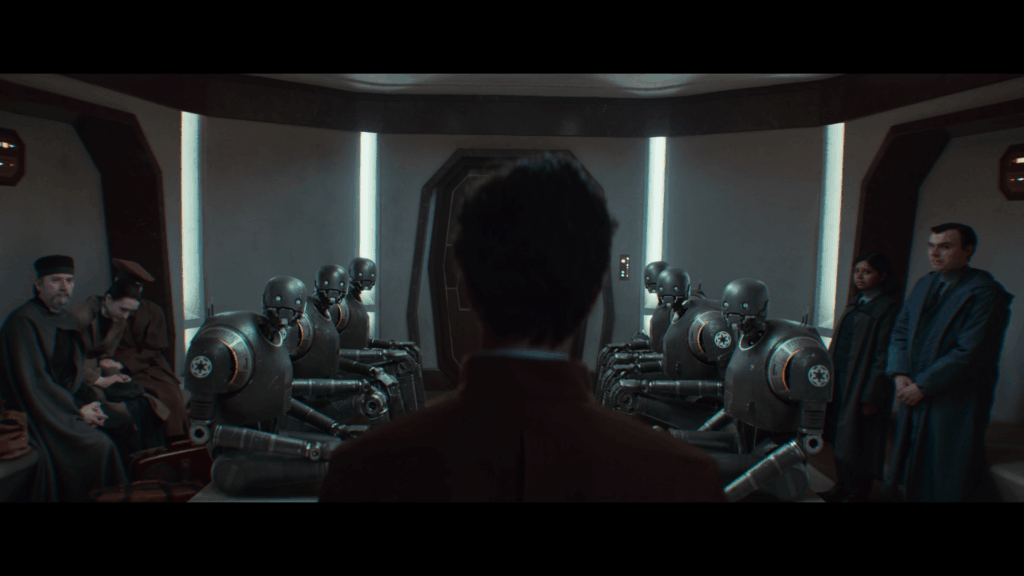

Andor remains an ambitious show however, and it can and does still aim high. There are perfunctory elements – I can’t say I was pleased to be reunited with sassy robot K-2SO, though the show makes some good (nasty) use of him as the Emperor’s designated replacement for the Jedi, a metallic Darth Vader who can be sent into the fray alone and hurl some bodies around. In a way it’s more of a testament to the narrow horizons of the rest of TV; Star Wars is ultimately a set of movies for children, so it’s acceptable that much of Star Wars is not so sophisticated as this; what excuse does everything else have?

The distinguishing focus of Andor‘s second season is gender, launching in with a run of three episodes which deliberately marginalise the title character (locked up in an unfortunately cartoonish side-story about some less disciplined rebels descending into infighting). In his place are three vignettes, properly considered, about gender and class in this nascent Empire. Tony Gilroy, with the writing credit on these first three episodes, opts to take us on a history lesson as we see a Marx-inflected view of family relations play out on screen.

From the top, the main through-line here is Leida Mothma’s marriage of convenience to the weedy little son of new money crook Davo Sculdun. Mon Mothma’s struggle between advancing the cause of the rebellion versus protecting her bacchanalian husband and tradcath daughter was carried to conclusion last season, making this an extended coda where we see, step by painful step, how much it costs her – but also how much she has gained, what she is escaping from.

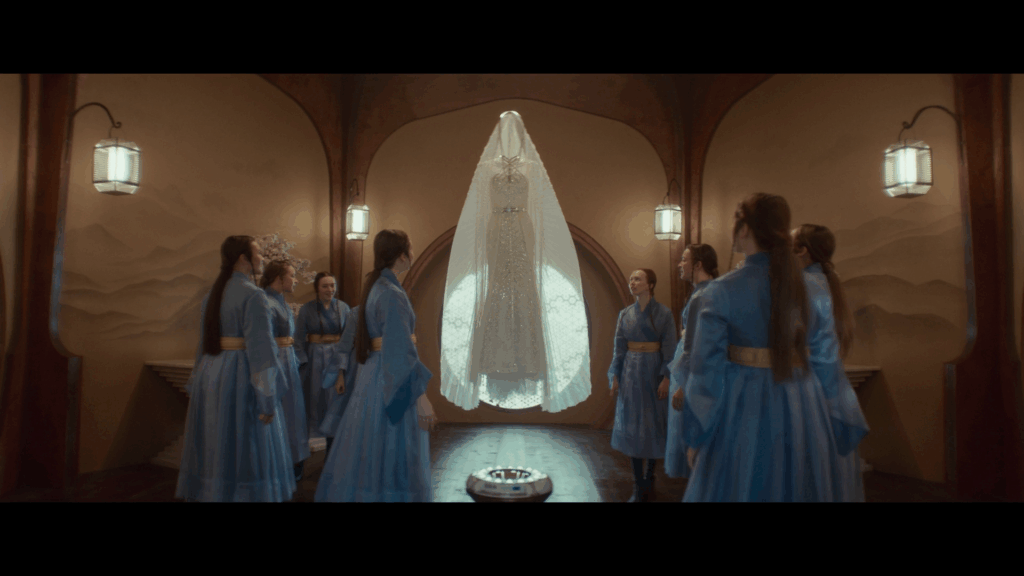

The aristocratic traditions of Chandrila are drawn with a light touch: a string of expensive parties, a ceremonial pilgrimage noted to now be on public land, a gruesome ceremonial dagger taking centre stage at the ceremony. Sculdun repatriates a great stone statue evoking a maternity goddess, and claims it a victory for all Chandrila – but to remain in private ownership. It is in a word patriarchal. The elephant in this room is Mon Mothma, the woman politician, more comfortable in the corridors of the senate than at this grotesque display of wealth. Her agency always an unspoken wall between her and her husband, at the last second we see her make a heartwrenching appeal to her daughter to escape this society as she did. Leida just wishes her mother could be normal.

The Republic, in permitting Mon Mothma to become a senator, has fractured these aristocratic traditions and with them the strict gender roles it enforces. The Empire is going to obliterate them. We get the first hints here of the Empire’s plan for the planet of Ghorman, as akin to Chandrila as Chandrila is to Naboo – the new Star Wars tradition of the same location in multiple instances in full effect, and Naboo itself does get a guest appearance in the final episodes as another Ghorman at another time. Ghorman, a producer of luxury goods with traditions as rich and complex as anywhere else, is to be mined for precious minerals. To do so, the privileged society of Ghorman must be dismantled. And to make this happen the Empire (in the person of a returning Ben Mendelsohn, of whom more later) has tapped up and coming intelligence supervisor Dedra Meero (Deborah Meaden should sue).

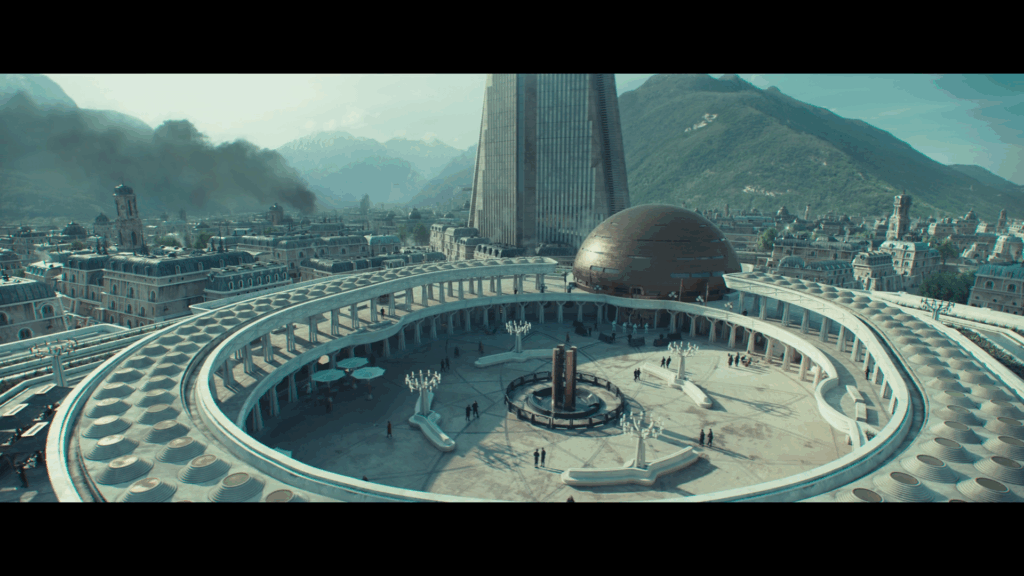

Much of this season of Andor concerns the question of Ghorman, which we see first introduced by a star-shaped city with a central courtyard that blends the iconic Naboo Plaza de España with the Trade Federation control ship in a particularly pointed bit of visual metaphor. The new armory constructed as part of the plot to subdue the Ghor is in the triangular shape of a Star Destroyer. Ghorman is in this way the fully Imperially-integrated Naboo, Imperial presence at first in an uneasy alliance with local business interests – the fashion houses of Ghorman make cloth with an exclusive local spider in a manner that alludes to various real-life luxury foodstuffs and products, though as everyone in Ghorman speaks cod-French, let’s say wine. Continuing that theme, there’s even a tolerated cenotaph in that main plaza solemnly remembering the Ghormans killed in a crass bit of murder years earlier by top-ranking Imperial Grand Moff Tarkin, in an incident that evidently didn’t hurt his career much.

In many ways the story of Ghorman is a re-telling of the story of Ferrix last season: repression creates the conditions for rebellion and a small problem for the Empire becomes a large one. But the details are all shuffled: where Ferrix was a working-class place with a strong community culture, Ghorman is individualist and bourgeois. M. Rylanz begins his rebellion coyly suggesting to Syril Karn (however cynically) that the true Emperor would surely be upset to hear his subjects were being mistreated so. And some elements are turned particularly bleak: the bloodthirsty Sergeant Linus Mosk, who on Ferrix was all too eager to crack skulls, is mirrored on Ghorman in the witless Sergeant Bloy, who doesn’t realise until it’s far too late that he’s being sent on a suicide mission with his squad of raw recruits.

Like Rylanz, Chandrilan elite act and dress the in the accoutrements of the Republic: Jedi-like robes in rich golds and blues. The wedding ceremony features a prominent cutting of a braid in a manner which recalls the Padawan braid won by Obi-wan, Anakin and the younglings. The braid is worn here by the woman. Through the course of Andor‘s second season, we gradually see the ratio of appearances at the Chandrilan parties shift, beige, white and black Imperial uniforms taking up more and more room. The Empire is snuffing out this outcrop of republicanism as it will eventually dissolve the Republic senate, and with it will go the archaic ceremonies and traditions that form part of the institutional power that until now this class has enjoyed. Replacing it will be those uniform beiges, whites and blacks with career bureaucrats like Dedra and Syril inhabiting them. The relationship between Dedra and Syril is similarly without artifice, defying tradition. Eedy, Syril’s mother, in many ways embodies the morbid republic, a slightly decrepit, casually cruel vampire on her son’s neck who sees in Dedra a second victim to torment. Dedra, with the exact bearing of a Napoleonic-era captain, simply prescribes to her in curt terms the positive relationship they are to have, taken or left. Eedy concedes.

This is the Faustian pact that Dedra is making, unlimited power to sweep away old assumptions about social hierarchy and gender roles at the only cost of becoming complicit in Empire, of being the finger that pulls any trigger ordered. And that violence can be both impersonal, as with the droids released to indiscriminately smash the Ghorman crowds, or it can be deeply gendered. The other environment we see equitable gender relationships expressed is with Bix, hiding out on the farm planet from Rebel Moon with last season’s most valued players Brasso and Wilmon. The farm workers share communal meals, raise children in common, and occasionally verge on child-like innocence in how egalitarian it all is (notably, the workers have a positive relationship with the farmer). Unlike Dedra and Syril however, this is neither sanctioned by the Empire nor is it an expression of the Empire’s power. It is radical beyond comfort, pointing to a world of relationships where no one role is dominant whatever the gender. An Imperial patrol is sent to take census of the workers, in effect an immigration raid, and the ranking officer finds Bix alone and attempts to rape her. Gilroy writes a horribly true-to-life depiction of a man using his modicum of power to gratify himself with meaningless cruelty and we can all cheer when he gets hit with a big space-wrench. There is no point to the rape much as there is no point to the census overall; the use is merely to remind everyone involved of what is what. Empire on the one hand dissolves traditional roles and washes away gender; on the other, it uses gendered violence as a stick as hefty as any other to beat down with.

The impact of these vignettes is cut off just slightly by some inattention later in the season. It’s unclear what we’re meant to take away from the scene where Cyril goes to strangle Dedra after learning that she’s betrayed him. Is she into it? Is he reverting to type? Similarly, Bix’s subplot over the next six episodes has her sinking into a depression, leaning into substance abuse, getting some therapeutic revenge with Cassian’s assistance, then getting into faith healing and leaving because of a belief in destiny? It’s unfocused and verging on cliche. Mon Mothma avoids this issue both by dropping her family connection entirely, the question of her as a woman and mother not returned to.

The show never quite settles into itself either with Kleya, Luthen’s daughter, assistant and collaborator. She gets a highlight episode here, complete with backstory elements that place her on Naboo at a time of Imperial occupation (her superlative, melodramatic dress sense explained in one link to Padme Amidala) and hyper-competent heist sequence – it’s a highlight of the entire show. But despite the obvious affection involved for Andor‘s femme fatale – and the Star Wars grand prize of getting to remove the machine keeping your father alive1 – Kleya ends the season still something of a cypher, clearly crushed by the loss of her adoptive father but with only a tentative reconnection to Cassian and Kel to express it with. The defence of Luthen to the Yavin leaders placed in Andor’s mouth instead.

All this said, while reviewers have so far contested the final image of the show, that of Bix standing in a field of wheat gazing at the sky, I did not mind it. To raise children is ultimately an act of faith in the goodness of the world, its capacity to improve. That goes for Bix and tiny Andor Jr. as it had previously gone for Marva and Cassian, Luthen and Kleya, Salmon Paak and Wilmon. It’s a literalisation of the chain of unconditional love that fuels the rebellion – the show certainly has not balked at non-standard family relations before this point. The communitarian society on Mina-rau is the closest thing Andor has to paradise, the figurative paradise that every rebel is working towards.

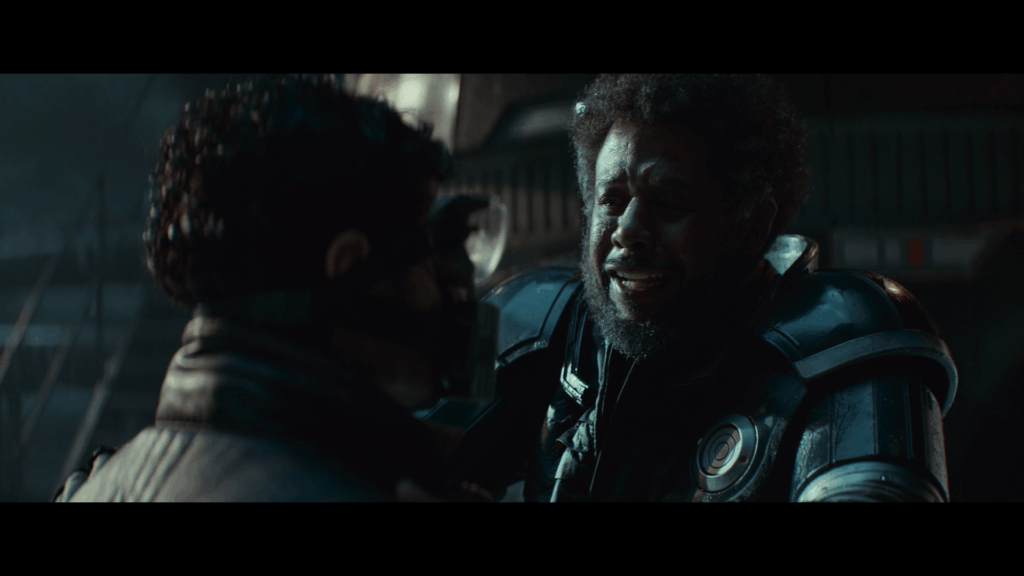

We revisit Saw Gerrera in the second run of Andor episodes, commandant to the kind of guerilla cell that his namesake (you know the one) might have recognised: tight-knit, testosterone-fuelled, a brotherhood constantly on the move. Wilmon, the plucky bomb-maker from Ferrix last season, is sent by Luthen to advise Saw on the operation of some deadly fuel extraction technology. But instead of teaching his lesson and leaving, Saw effectively kidnaps him – and worse, intimates to the student that once the teaching is complete, Wilmon will be disposed of. The setup leans into the audience’s instinctual fear of rebel movements “going too far”, of charismatic leaders turning political coalitions into cults. Saw Gerrera as a second Vader, making unilateral life-or-death decisions on the performance of his underlings. The twist is that the opposite is true: Saw is a more effective operator than ever, deftly outmanoeuvring an Imperial plot to oust him. His apparent irrationality, he explains to Wilmon, is simply acceptance of death. He will burn brighter and live freer, no matter the cost.

The irony here is that Saw and his old sparring partner, the new, more irascible Luthen, have converged: when Luthen reveals to Andor in the next run of episodes that he sees no way out for them other than a noose, the comparison is complete. Luthen does not have Saw’s lust for freedom, but the life of a spymaster is such that he is always looking over his shoulder, always rooting out hidden plots, always telling his friends less than they might want to be told. And like Saw, he is now being marginalised, the rebellion he has helped build coalescing into something that won’t need a spymaster with the ears of the Imperial senate. A rebellion that can fight in the open, for hearts and minds. A desperate Luthen tells Mon Mothma that he doesn’t have any evidence and he doesn’t know who or why, but the people she’s expecting to meet the next day are a danger to her and she’s just going to have to believe him. It’s not the kind of appeal you make twice. In the subsequent episode, a year on, Luthen rues mournfully to Kleya that they may have run out of ‘perfect’. Luthen, boxed in on Coruscant, accepts the inevitable, much as Saw with on Jedha shortly thereafter.

I’m interested to revisit Rogue One and specifically the character of Saw, who was very poorly served by that film’s torrid production history. His featuring in Andor, which you have to assume has been limited by the amount of time they were able to retain Forest Whitaker for on any given day, has punched way above its weight – a character with real revolutionary fervour in a series much given to prevaricators, cynics and wide-eyed imbeciles (sorry Luke). Again like Luthen, Saw is a character who wants to win and knows what that will entail. Unlike Luthen, he is ultimately not willing to cede control to the bureaucrats and artistocrats who will ultimately form the New Republic.

Cassian has another conversation shadowed with death, right at the end of the show, where a skeptical Bail Organa okays his mission that kicks off Rogue One. They discuss the abstract threat of the Emperor’s new weapon, unaware that in a matter of days it will have killed them both. This is the ultimate strength of Andor as a project, to draw these lines across decades of fiction, and something that simply could not be done without the Star Wars connection.

A trend that particularly upsets me in lots of media lately is lack of discipline; this was particularly galling in Ahsoka, where any notion of belonging to a hierarchical organisation was functionally jettisoned for Green Mary Elizabeth Winstead to make some faces instead. But it goes beyond Star Wars: even in an ostensibly serious drama like Shogun there often was a casual attitude to hierarchy entirely at odds with the setting. Lesser shows often feel like remakes of the Onion article “Entire precinct made up of loose cannons”. Real life militaries run on discipline, historically brutal discipline. Real life bureaucracies run on hierarchy. Which is not to say you can’t have a Captain Kirk, going outside the stuffy rules of the Admirals to do what’s right, but that can’t be the rule – and the people present who do follow the rules have to behave accordingly. Watching recent Doctor Who episode ‘The Well’ there’s a scene where the number two relieves the ranking officer of command because he disagrees with her decision making; in the real-life British Navy that would have had him hanged.

This remains an area Andor excels in. Throughout the second season we catch background glimpses of a structured rebellion that is going to outpace and surpass both Luthen’s spy rings and Saw Gerrera’s independent cells. What was disparate clumps of useless or dangerous individuals like the group who take Cassian hostage in the first run of episodes, by the climax of the ninth episode has become the rebellion of A New Hope, a full-blown military organisation with ranks and procedures that Cassian himself is starting to look like an odd fit for. Infamously, when the rebellion presents Luke and the gang with medals at the end of A New Hope, Lucas staged it by reference to shots from Triumph of the Will. It’s a parallel power structure to the Empire now, if a diminutive one, and there’s a great verisimilitude in seeing Alastair Petrie warn Cassian that mercurial disappearances and secret missions will soon have no place in this new organisation.

The rebel bureaucracy is naturally a bagatelle compared to the Imperial one, and Andor‘s second season benefits from an increased role for Anton Lesser’s evil spymaster Major Partagaz. ISB head honcho Partagaz is the picture of senior leadership, prowling in circles around his cavernous meeting room, well aware of the fear he inspires in his themselves otherwise authoritative underlings. It’s instructive as well as practical, each officer bringing to their reports some form of the same intensity and cruelty. One of the stand-out moments in the season is Dedra and Partagaz debriefing an ebullent Syril, still labouring under the impression that his mission is related to the quest to capture Cassian Andor. Describing the Ghorman rebels he has been made double agent to, he calls them “inexperienced but eager”. Partagaz, looking directly at Dedra, deadpans “How often those attributes align.” If the message to Dedra wasn’t plain enough, he follows up once they’re alone with a direct warning that her involvement of the goofy Syril is a liability. They are not Andor and Bix; there is no balance of “what we’re fighting for” versus the fight itself. When push comes to shove, Dedra’s position – as Captain Kaido puts it – is to be a finger on a trigger, and to respect the chain of command. If the command is that inexperienced recruits are to be sent to face the angry Ghorman mob, so be it. If the command is that an imperial sniper is to provoke mass violence, so be it. And if Syril, who has always dreamed of heroics, is not content to hide in a back room with civilians and children then the failing is his alone.

This unwinds in the way any system that cannot evolve or compensate must die: the inhuman rigidity, the adherence to protocol, the competitive contempt between peers leaves the ISB unable to correct course as a string of bungled operations collapse into one another – Dedra’s desire to be the one to collar Luthen (‘Axis’, in their wonderfully Le Carre-esque dictionary) leads her to go it alone with minimal backup. This is to pip former protege Heert to the post, and as a true student he immediately turns around and does exactly the same thing in trying to bring in Luthen’s own protege Kleya.

Syril of course, who only ever imagined himself to be in favour of the Empire, falls by the wayside dying in a Javert-esque farce, desperately trying to hide the massacre unfolding on Ghorman from himself by slapping the cuffs on an incidentally-present Cassian. “You didn’t seem to mind the promotions”, an indignant Dedra barks at him. But the idea that there was a quid-pro-quo at work is alien to the ultimate just-world believer, who has never been able to imagine that good people might break the rules or that bad people might make them.

But Dedra hasn’t just doomed herself with this domino cascade: to keep up with Heert she’s been surreptitiously retaining documents she shouldn’t have access to, and when Luthen’s man on the inside of the ISB Lonni steals her access, he finds not only her plan to bring in Luthen but the details of the big secret itself, as yet unmentioned by name in Andor. It’s the Death Star, as an incandescent Krennic has Dedra stammer out, and this leak will go on to take out Partagaz (two subordinates dead, one imprisoned, his ‘resignation’ is asked for in terms he understands), Krennic himself (as per Rogue One) and the looming figure of Tarkin at the penultimate step of the pile (if you haven’t seen A New Hope, he dies when the Death Star explodes). The problem at its root is one of trust and faith: if the ISB supervisors could trust each other, they could collaborate effectively. Lonni’s spying is enabled by his ability to project himself as the rare friend around the ISB table. Luthen is utterly ruthless but at root what he does have is friends everywhere. The ISB supervisors have friends nowhere, the Empire ultimately as rewarding to Dedra’s faith in it as it was to the Ghor. Andor comes to rescue Kleya; no-one comes to rescue Dedra, who in a cheeky bit of cosmic karma ends up in a Narkina 5-style prison, presumably labouring to build a second Death Star.

Andor‘s inarguable quality has been a catalyst for critical consideration of Star Wars, which is scarcely a positive outcome. Much better to be something quietly competent like Skeleton Crew than something that rouses the great beasts like The Acolyte! But yes, Andor has inspired comment, much of it of a kind – quickly summarised, that Andor is Star Wars done right, that Disney Lucasfilm will struggle to reproduce the quality of Andor, that Andor is not in fact Star Wars at all, and finally that George Lucas is a hack who not only cannot have inspired something like Andor, he probably also stole the reels for the original film from an editing bay in 1977. The last one demonstrates to me a startling lack of intellectual curiosity – akin to, on reading Naoki Urasawa’s masterpiece Pluto, declaring that you’re glad someone has finally shown Astro Boy to be so much garbage. Andor is not made by people who hate Star Wars, and so it cannot be made by people who hate George Lucas. The idea is childish. The alchemy of the approach is that Star Wars is for children, and always has been, but things that are for children can be valued and reinterpreted and played with. Star Wars permits Andor to reference a visual dictionary that the audience will intuitively understand. In this way the question of whether it is or isn’t Star Wars is moot. It is a Star Wars story.

The nature of Andor – a complementary story about the lives of people who weren’t gifted with providence, who aren’t related to great leaders or born to great destinies, makes a fine companion to the original films. It makes text of subtext, improves on both, and provides an excellent counter-argument to anyone who ever suggested that Star Wars should have less intergalactic politicking.

Which only leaves the question of whether something this good will come along again for Star Wars, a question the world politics of which are too unpredictable to answer. I hope so.

Previously:

- Obi-wan: Episode 1

- Obi-wan: Episode 2

- Obi-wan: Episode 3

- Obi-wan: Episode 4

- Obi-wan: Episode 5

- Obi-wan: Episode 6

- The Phantom Menace (video essay)

- Andor: Episodes 1, 2, 3

- “Can Andor save Star Wars from itself?” Andor: Episodes 4, 5, 6 (plus supplemental)

- Andor: Episode 7

- Andor: Episodes 8, 9, 10

- Andor: Episodes 11, 12

- Ahsoka: Episodes 1, 2

- Ahsoka: Episodes 3, 4, 5, 6

- Ahsoka: Episodes 7, 8

- The Acolyte

- Andor: Season 2

If you want to read something non-Star Wars by me try ‘The Cult of the Scan‘, about the attraction of bootleg 35mm film print scans. The new site has an RSS feed, you can also subscribe to my Letterboxd reviews if you see fit.

- I believe I stole this excellent joke from someone. If this is your joke please let me know. ↩︎