“Any idea who that guy with the red eyes is?” he asked Ghent.

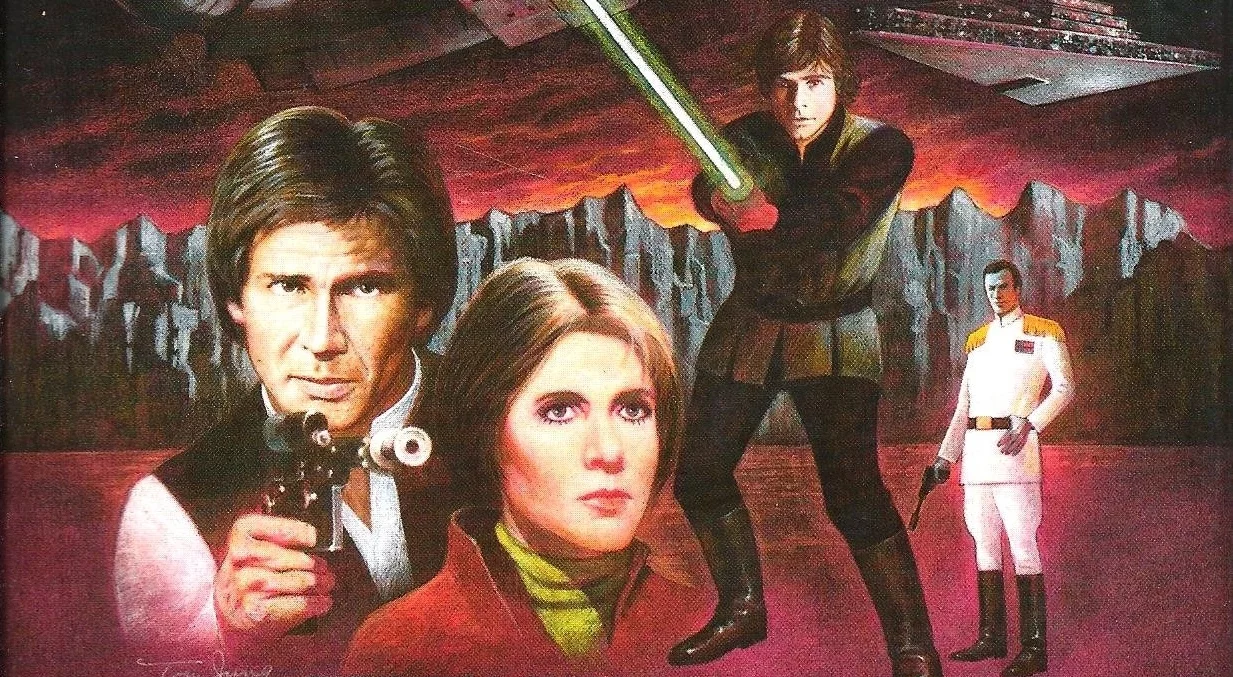

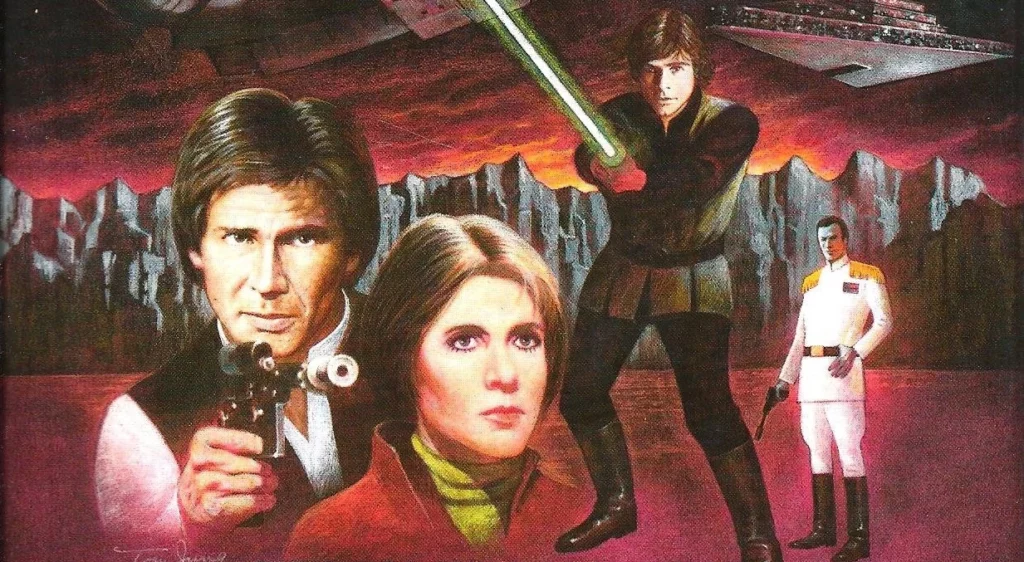

Heir to the Empire

“I think he’s a Grand Admiral or something,” the other said. “Took over Imperial operations a while back. I don’t know his name.”

Han looked at Lando, found the other sending the same look right back at him. “A Grand Admiral?” Lando repeated carefully.

“Yeah. Look, they’re going—there’s nothing else to see. Can we please—?”

“Let’s get back to the Falcon,” Han muttered, stowing the macrobinoculars in their belt pouch and starting a backward elbows-and-knees crawl from their covering tree. A Grand Admiral. No wonder the New Republic had been getting the sky cut out from under them lately.”

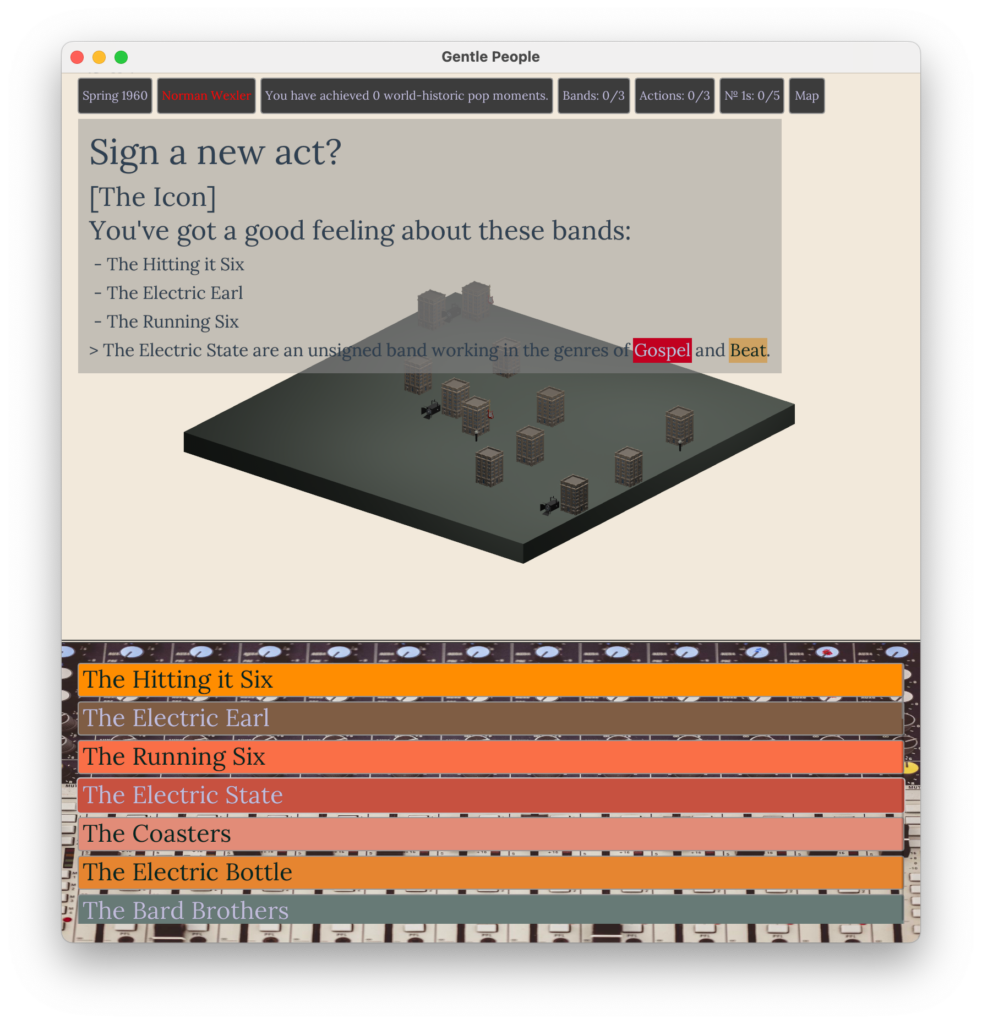

We all love Heir to the Empire, don’t we? Timothy Zahn’s magnum opus of Star Wars fiction that introduced the world to the blue-skinned, red-eyed Admiral Thrawn, the Imperial Remnant’s one and only Grand Admiral. A Grand Admiral, I hear you say? Yes, a Grand Admiral. But if you forget the unique threat posed by a commander of such senior rank described above then don’t worry, Zahn’s sequel Dark Force Rising has one or two reminders for you:

With a Grand Admiral in charge of the Imperial Fleet again, perhaps there was now a chance for the Empire to regain some of its old glory.

“A Grand Admiral,” Ackbar said at last, his voice sounding even more gravelly than usual.

“We’re dealing with a Grand Admiral, Han,” Lando reminded him. “Anything is possible.”

“Great,” Han growled. “Problem is, with a Grand Admiral in charge of the Empire, we might not have that much time.”

“Especially with a Grand Admiral in charge of the Empire,” Han pointed out. “If he catches you here alone, you’ll have had it.”

Mara looked into those glowing eyes, beginning to remember now why the Emperor had made this man a Grand Admiral.

A small shiver ran up Mara’s back. Yes; she was remembering indeed why Thrawn had been made a Grand Admiral.

But he was a Grand Admiral, with all the cunning and subtlety and tactical genius that the title implied. This whole thing could be a convoluted, carefully orchestrated trap… and if it was, chances were she would never even see it until it had been sprung around her.

“The glowing eyes bored into her face, the question unspoken but obvious. “What was here for me before?” she countered. “Who but a Grand Admiral would have accepted me as legitimate?”

“The Empire’s being led by a Grand Admiral,” [Han] muttered. “I saw him myself.”

The silence hung thick in the air. Mon Mothma recovered first. “That’s impossible,” she said, sounding more like she wanted to believe it than that she really did. “We’ve accounted for all the Grand Admirals.”

…if the Imperials got their hands on the Katana fleet, the balance of power in the ongoing war would suddenly be skewed back in their favor.

And under the command of a Grand Admiral…

[Mara] took a deep breath, forcing calmness. She would not fall apart. Not here; not in front of the Grand Admiral.

“If there is,” Mon Mothma interrupted firmly, “we’ll soon know for certain. Until then, there seems little value in holding a debate in a vacuum. Council Research is hereby directed to look into the possibility that a Grand Admiral might still be alive.”

“With a Grand Admiral in command of the Empire, political infighting in the New Republic, and the whole galaxy hanging in the balance, was this really the most efficient use of [Luke’s] time?”