Ringing in my ears as I enter the cinema is Pulp’s old-new single off their latest album, Got To Have Love. I don’t know how seriously I’m supposed to take this self-directed admonishment from leading man Jarvis Cocker, who so often inhabits a grim, seedy persona as the protagonist of his songs. I’m here to see the Superman film that is also about how we’ve got to have love, or kindness, or something. In its worst, most tawdry moments the script tries to get away with calling this attitude ‘punk rock’. It’s not, and the comparison lands uncomfortably similarly to those awful right-wing op-eds that call Conservatism ‘the new punk rock’ every five years. But it’s Superman, back on screen, and if Cocker can breath life back into these hoary old aphorisms then there’s no reason that seeing a straight depiction of mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent back on the big screen shouldn’t be cause for celebration.

Before we go further, permit me to address my motivations directly to the camera – as so many characters in this film choose to do: I was dubious in my anticipation of this film. Superman (2025) is the latest effort by DC and Warner Bros to make seaworthy their idealised Whedonesque universe of heroes. It didn’t work in Justice League (2017) and it didn’t work in The Flash (2023) and that it works here is down to the careful efforts of new CEO(!) James Gunn in the twin caps of writer and director. Gunn draws liberally from the previous cinema outings for the ‘big blue boy scout’ in a manner that recalls Matt Reeves’ The Batman, and as with that film there is a note of the grim reaper’s chill hand in realising that there has now been 9 years since Batman v Superman, 12 since Man of Steel, 19 since Superman Returns and 46 since Superman (1978). It’s a haunting reminder of the passage of time, seeing these films (most of which I was around for the release of) plundered for many of their best ideas, repackaged for a new generation of cinema-goers.

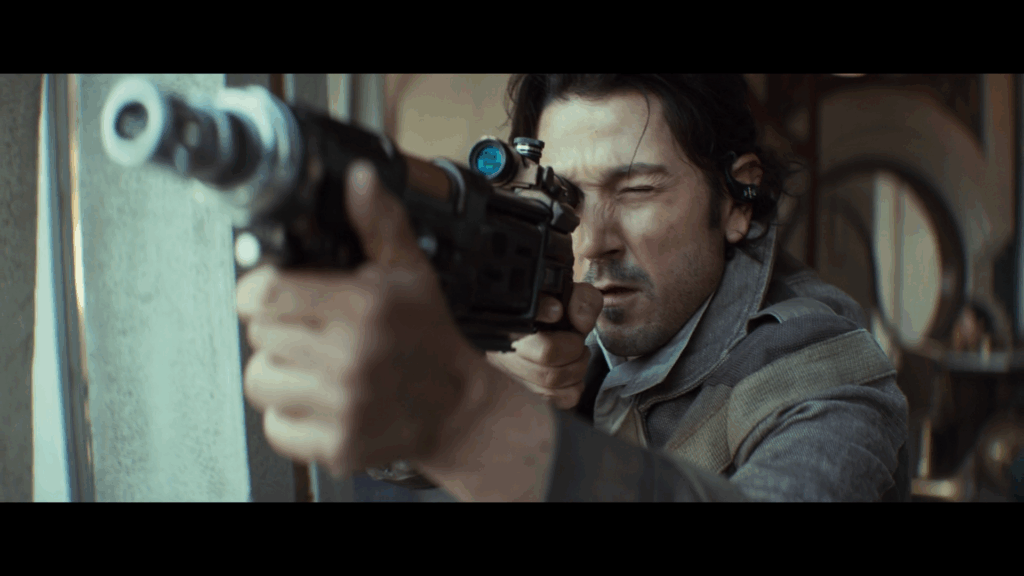

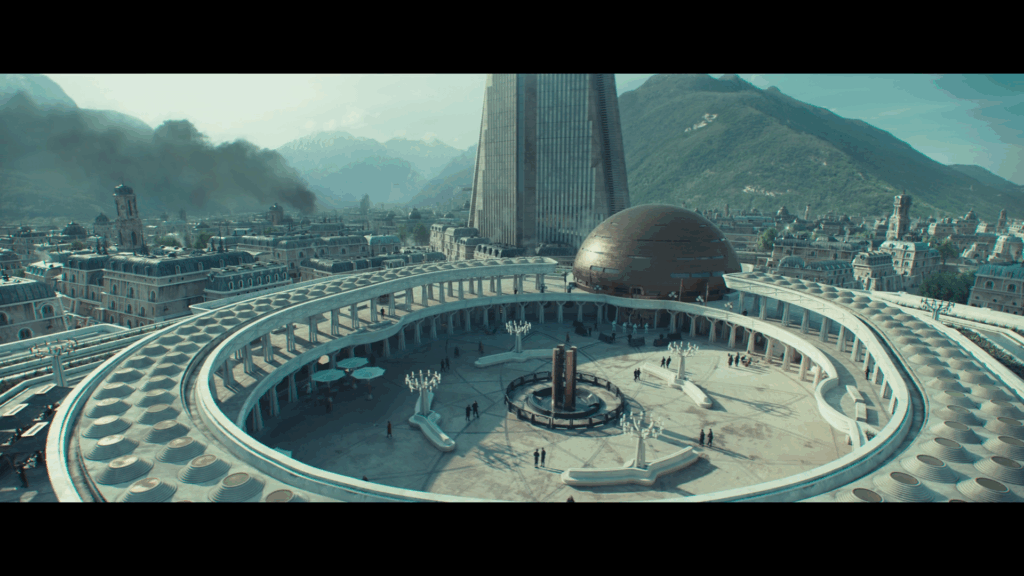

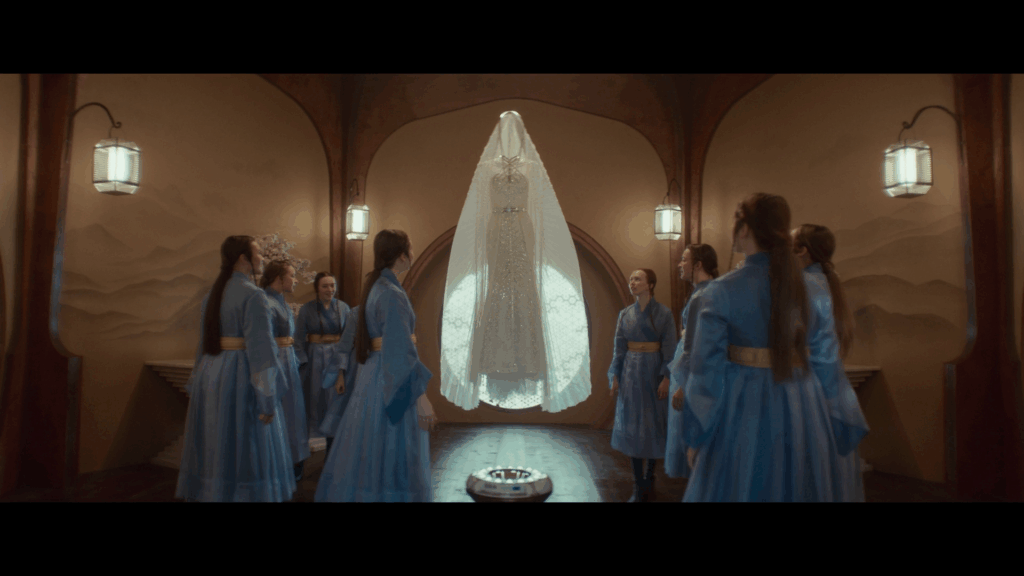

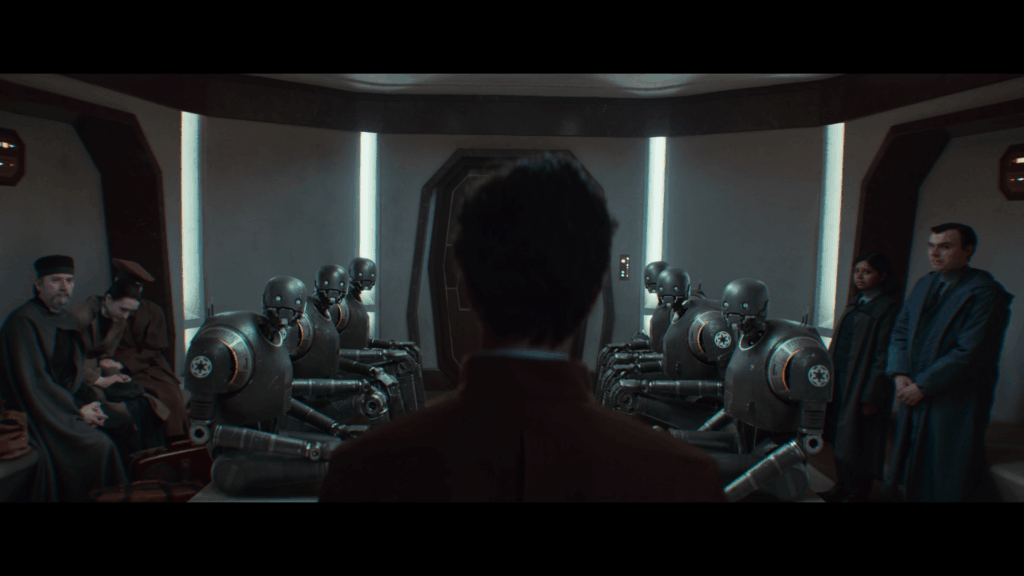

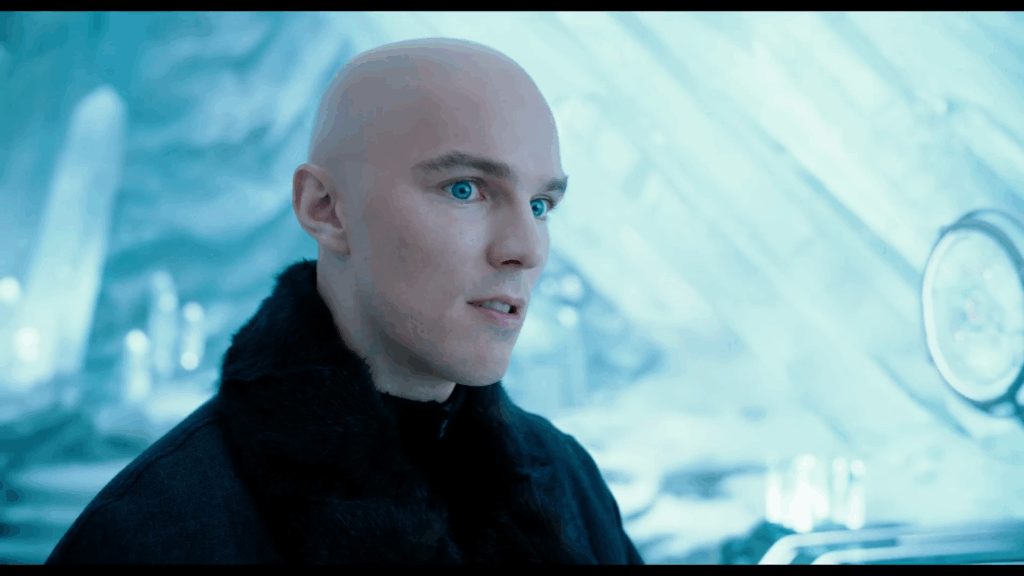

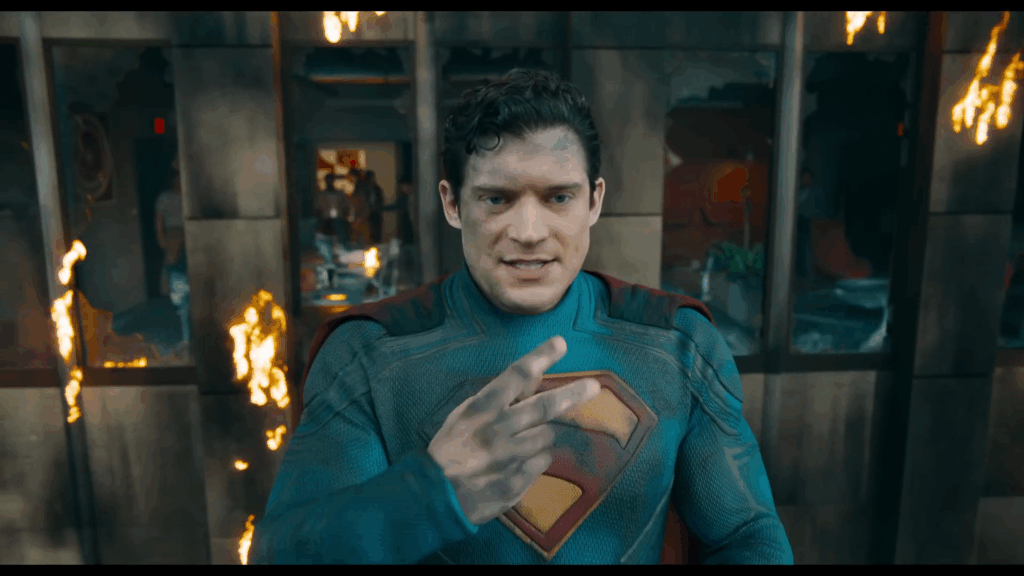

Indeed the earlier films aren’t so much referenced as ransacked: The visual design pulls from the Donner and Lester films, particularly in the elements of Krypton present. There’s a plot point pulled directly from Sidney J. Furie’s The Quest for Peace which is so prominent that it feels strange to call it an Easter Egg. There’s even a particular attention to eyeballs which speaks to an influence from the disgraced Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns. And the plot, at least until the final act, is something of a greatest-hits-tour of imagery from the two Zack Snyder movies: Superman cooking breakfast for Lois, a naive Superman intervening in foreign affairs, Superman placed in handcuffs while surrendering himself to the state. Lex Luthor turning opinion against Superman, Lex Luthor pitching killing Superman to politicians, Lex Luthor creating a monster for Superman to fight. It’s all transliterated into a post-streaming world of characters who state their feelings and intentions out loud, and action which sits solidly within a centre vertical for TikTok, but it’s recognisably the same stuff. Where there are changes, it’s to externalise and literalise: In the aftermath of his conflicts, Snyder’s Superman had to sit with the existential anguish of free choice. Gunn’s Superman has to sit with robots holding him down in the big agony chair that shoots fire at you because it hurts to be a hero.

I’m being droll but that’s not necessarily a criticism; there’s nothing inherently wrong with simplifying and literalising, though it means that this Superman is ironically often a bit more alien than he might otherwise be, oscillating in his scenes with Rachel Brosnahan’s Lois Lane between a kind of post-teenage petulance, demanding that the world be simpler so that he can act without consequence, and a detached aloofness. Fortunately Brosnahan brings her considerable talents to making the relationship seem plausible, with a nice subtle humour to the idea that – tormented by her own relationship demons – she is in a sense settling for Superman.

One of the more perplexing elements of Superman (2025) is that in the final analysis, Superman isn’t the one to deal the meaningful blow to the hotheaded Lex Luthor. Rather, Superman being occupied contending with his nondescript clone Ultraman, the intrepid reporters of the Daily Planet crowd into Mr Terrific’s Owlship and hover over the ruins of Metropolis as they publish a front-page takedown of Luthor’s crimes to the internet. Exposed at last, and savaged by the unruly Krypto in a strange bit of dark humour, Luthor is ushered into the back of a vehicle by some of the heavily militarised operatives he spent the film directing. Presumably this sequence of events is intended to split agency over the film’s climax between Superman himself and Lois Lane, reporter at large, and it’s broadly successful. The Planet gang are a distinct if glossy bunch, and Wendell Pierce plays a delightful but brief Perry White, editor, as a man who only seems to own one cigar.

It’s not unusual for blockbusters to get a little All the President’s Men when depicting journalism. The myth of the crusading journalist cuts across the 20th century, from John Reed to Hunter S. Thompson. But it’s a curiously narrow take here, not even going as far as the depiction in Batman v Superman of legacy media as an honest institution in ignoble decline. The Daily Planet gang are happy, healthy, gainfully employed, and all operate out of a lush downtown office space with dedicated cubicles – hell if you’re Neo trapped in the long 90s, but positively anachronistic for a world where WeWork has been and gone. It’s curious that the plot doesn’t go anywhere near touching on the idea of Lex buying the Daily Planet, something both Smallville and the Adventures of Lois and Clark took their swings at. Jeff Bezos put his fingers on the scales at the Washington Post to keep it from endorsing a candidate in the US Presidential election; it seems odd to portray fictional journalists free from editorial intervention when the real-life ones evidently aren’t.

You might contend that the film is really just a piece of fluff, an object of wish fulfilment and that earnest journalists who speak truth to power are of a set with the flying man with laser eyes – a cynical take, but reasonable. But the film is really very concerned with this question of the good journalist, and touches on it a few times. Lois and Clark come to sharp words in an early scene over Lois’s insistence on interviewing Superman as she would any other political figure: over her refusal to ‘print the legend’, which we are meant to assume Clark has been doing in his ethically questionable self-interviews. In a bizarre aside, Clark insists that he – Superman – doesn’t engage in social media, before naturally revealing an encyclopaedic knowledge of what people are saying about him on it. Implicitly, that’s why he needs to write these dishonest features about himself: to put right the braying masses who are speaking ill of him. Now this is not Superman’s finest hour, and so the film is quick to offer an excuse for him. During the interminable pocket universe sequence, there’s a quick visual gag in which Lex Luthor claims to have a host of barely-literate apes tasked with running Superman down online. A quirkly take on the notion of bot armies manipulating opinion for pay, this must be a comforting notion for Director Gunn, who infamously lost his job – but then quickly regained it – after a social media storm over the content of some of his old tweets. Among the feckless prisoners in Luthor’s space prison is, we are told, a blogger who wrote a negative profile of him. Presumably they’ve been preserved as the last of a dying breed. If the general quality of discourse is so poor, the suggestion seems to be, then it’s impossible to say if Superman or Lex Luthor or anyone else is good or bad – unless it’s printed by the authorities at the Daily Planet.

A final discordant note on social media comes with the depiction of Eve Teschmacher by a vaguely scene-stealing Sara Sampaio. Lex Luthor’s partner, she’s a constant presence alongside him taking an endless array of selfies with goofy expressions on her face, as he goes about his many crimes. Exactly why he indulges her in this is never touched on, and the degree to which she is intentionally cataloguing his sins is also frustratingly vague. For some unknown reason she’s head over heels for Skyler Gisondo’s unpleasant Jimmy Olson, who in a strange and mean-spirited bit has issues with her physical appearance. Via Olson, Teschmaker gets her crucial smoking gun of photographic evidence to Lois for publication at great personal risk, despite which Jimmy continues to shun her. In this way Eve really takes second credit for exposing Luthor and it would have been nice for her to have her moment in the Owlship also. The absence of such means that the film makes an odd distinction between the serious Lois Lane and the slightly infantile Teschmacher, as if placing them on an even keel might sully Lois with Eve’s girlish vices.

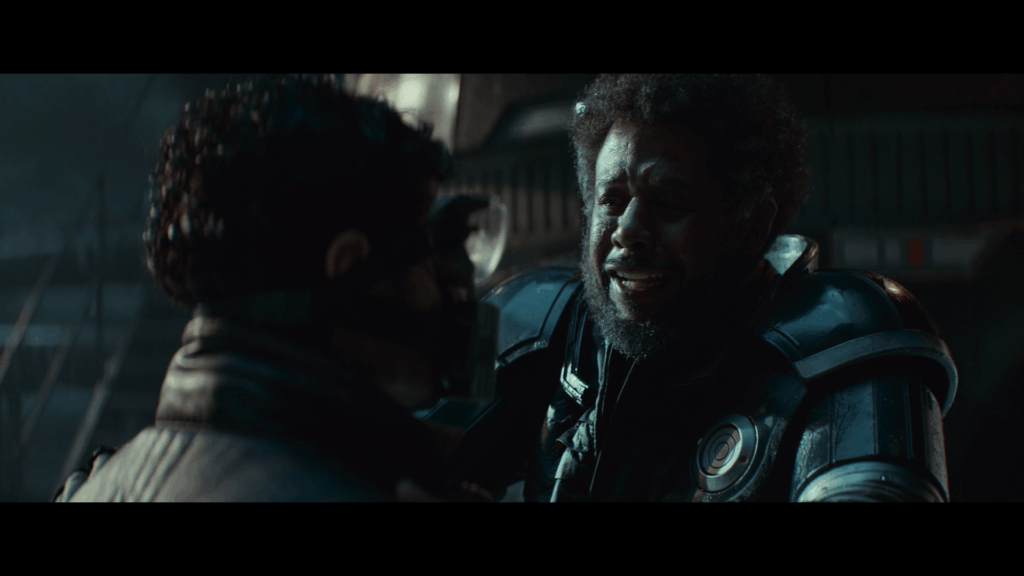

This aside, if there’s an Achilles’ heel to this Superman it comes in how the slightly disjointed plot doesn’t quite gel, and I’m no stranger to the prospect of stitching together multiple disconnected takes on a subject into a single whole which thus gains the appearance of deliberate creative intent. Early screenings of this film apparently made overt the formal structure of it, with title cards for each day of events proceeding linearly through a week of Superman’s life. But there’s an odd tension between the different ‘days’ of the film, some of which seem to be saying very different things to each other – the climax insists that the citizens of Metropolis can perfectly evacuate at a moment’s notice, when much of the rest of the film has hinted that they’re becoming dangerously carefree about superhero action. The absolute outlier is the aforementioned pocket universe sequence, which is visually uninspiring, reminiscent of the ugly Ant-Man 3, as well as trivial to the plot – Superman is locked in a room with only a deeply conscientious man to guard him. Whatever could happen next. Lois and Mr Terrific (a fantastic Edi Gathegi, who just sort of wills his character into having a bigger role than he does) stand in one spot for the majority of it, gazing at a distant green screen. And most oddly, Lex Luthor gets his big villain moment here: he’s picked out a man, Malik, who showed Superman basic human kindness earlier in the film, and he’s had him bound and gagged and brought before Superman, wherein Luthor shoots him in the head. It’s kind of sped past in the moment but it’s a real dark turn.

Especially for a film that’s about to proceed into a third act where we are repeatedly assured, in excruciating detail, that no-one is harmed or hurt. What makes this guy so unspecial that Superman – who volunteered himself to the position where he’s unable to act to save him – gives up? Steven Moffat’s Doctor Who episodes used to have a recurring refrain of “Just this once, everybody lives!” where an episode that had seemingly settled into the regular fictional logic of tragic but unavoidable loss would rebound, go one step weirder and have the outcome be no loss at all. It’s a neat trick, and of course it’s the ending to Superman (1978), where Superman reverses time to keep Lois from dying. Not every Superman film has to be Man of Steel; if you’re making something purportedly inspired by All-Star Superman then I want to see Dr Leo Quintum popping in at the end with a hundred clones of Malik ready to go.

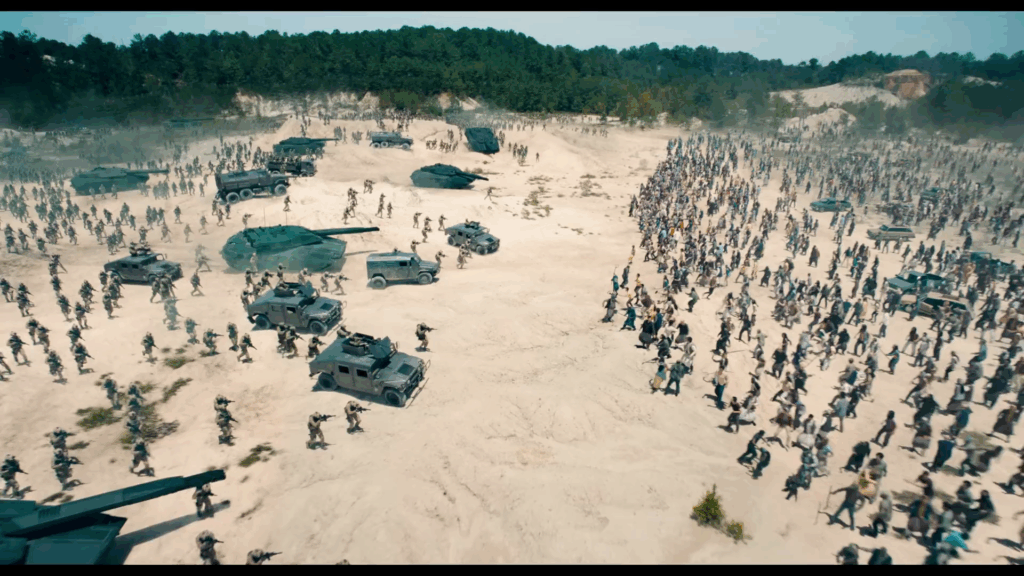

The politics of the movie are the kind of cypherous mush that has been typical of the genre going all the way back to Iron Man: war is bad, but also the fault of a bad man who can be individually picked up and struck off if we only had the moral fortitude and a smart enough missile. Everyone else, from the top to the bottom, is only following orders. This goes for Luthor’s oddly diverse goon squad as well as fictional foreign actor ‘Boravia’, with the movie’s clash between a Boravian military detachment and an gathering of innocent civilians on a nondescript (although strangely small) sandy outcrop being the closest it ever gets to looking like The Flash (2023).

Any real dive into the morality of the film is blunted not just on the ‘be kind’ platitudes but also the shifting message between the different chunks of film; early on Superman is criticised for his naïveté, at the end of the film he’s commended for his inspirational rigidity. Killing is always bad, except when it’s the cowardly and murderous Boravia president, or you’re doing the ending of Batman Begins and allowing public transport to bring your antagonist to an untimely end. Even ‘be kind’ folds in the face of ‘let your dog knock a guy about if it’s funny’.

On a grandular level, in maybe the strongest sign of a botched script edit job, Mr Terrific appears in both a scene in the middle of the film where he’s strangly unconcerned with random antagonists milling about him as he works to shut down a portal, and a scene at the end of the film where he chews a guy out for attempting to assist him in closing the rift. Neither sits particularly well, given that the stakes for closing the rift are meant to be “the world is destroyed” and the portal in question was the one for taking people to Luthor’s extrajudicial space prison. The culpability of ordinary people is just not something the film concerns itself with – agency belongs to prime actors, business CEOs and presidents, the proud and free press, and superheroes.

Well, it’s not punk rock. In fact (you may be surprised to hear) it’s often quite cringe-worthy, the cynical (multiple lines confirming that someone who just fell down from space is ‘still breathing’) clashing with the earnest (Superman being so committed to 100% rescues that he’s moving squirrels about while a giant monster thrashes about). The action is mostly a bit naff and the acting is carried by a few strong players making the most of scraping their bowls clean (Nathan Fillion here operating at the elastic limit of his talent). It’s a $200 million dollar movie that leans heavily on putting a funny dog in centre view, like an episode of Britain’s Got Talent or a sequel to Soccer Dog.

But it’s coherent, and it’s fun – something DC’s films have generally only managed one or the other of for several years now. Corenswet is a charming enough presence that you want Superman to win even though he’s an idiot, and he has genuine chemistry with Brosnahan that makes you overlook all the yelling he does. The robots are funny. Is it the bedrock of a whole new franchise of films, fifteen years of sequels as James Gunn has promised? I won’t hold my breath, and I won’t watch Creature Commandos, but stranger things have happened.